Socrates-Platos

Along with the fact that we are neither

Buddhists, nor Adishankarists, nor biblicists, nor koranists,

nor Spinozists, and so on, we are no Socrato-Platonists. We are

just the brothers of people who were much more than animals that

used to make noises or counts

(Rev of Arès vii/10), and who used to seek the Path

to the Light.

As for us we met with the Light at Arès, but we

have to be aware that the brothers that have sought and

approached the Way, so that their thoughts and

written works may help us as penitents and harvesters

whenever we have to go our ways through the complicated dark

corridors of the world, which we have to change

(Rev of Arès 28/7).

We belong in a class of life linked to Life (Rev of Arès

24/3-5, 25/3, 38/5, xix/26), whether it is called God, or

Father, or Breath, or Allah, or Brama,

or Great Spirit, or Good, and so on, and we have a

guide: The Revelation of Arès, that does not start a

religion, or a policy, or a philosophy, but that drives us to

link up the lower dust to the absolute Higher Being, whose Children

we are (13/5). That ascent, which

still preys on the present, is an adventure attempted by many

people like Socrates and Plato, who are inseparable because the

former would be unknown, had the latter not made him known.

Socrates and Plato go with us in our spiritual adventure,

because twenty-four centuries ago they already thought over some

problems which we still have to solve. They are ageless,

because human beings are One, whether past, or

present, or prospective.

This is a somewhat long entry, because I have to define Socrates

and Plato's thought optimally, which is not that evident in this

age.

____________________________________

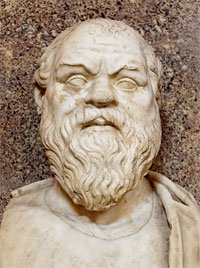

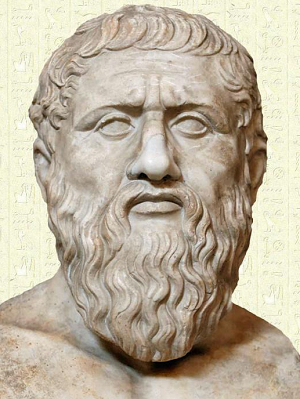

Socrates (on your left) and Plato (on your

right) used to preach a world where power could be just right

management, a world with no crown or honors, no lies, no

flatterers or flattered men, a world connected to the Higher

Being, from whom we are descended, a world close to that which we

hope we will re-create. The time and the human community, in which

Socrates and Plato lived, were intellectually, metaphysically,

literarily rich, so much so that it is very difficult

to cut off the two thinkers from the spiritual luxuriance of

their time. I have chosen a way of presenting the respective

thoughts or the only thought (which of them? nobody knows) of

Socrates and Plato among a lot of possible ways. In the following

text there are a few repetitions for the purpose of helping

readers in words that have different meanings nowadays.

Metaphysics, which is perception of the deepest causes of

the Universe, and which is foreseen by few spiritual intelligences

(Rev of Arès 32/5), has never had any weight in the

thoughts of the mighty on Earth. This is the problem amidst other

problems, which was already studied by Socrates and Plato in

Greece for centuries before now, a hundred years afer Buddha's

days in India, a thousand years after Zoroaster's time (Sarsushtratam

Rev of Arès xviii/3) in Persia.

Socrates did not leave anything behind, but Plato, who had ben a

disciple of Socrates, left a big written work in the form of

dialogues in which he used to feature Socrates. Plato sees the

sensible world as one contingent upon "essenses" or "ideas", two

words which have got other meanings today, but which he considers

as the only intelligible forms, the patterns only discernible and

easy to observe on Earth. At the top of those "essences" the

"idea" of good is displayed, which oversteps them in

dignity and power: God.

The Platonic written works have a form of dialogue to show how

primordial the exchange between human beings is, so as to go

beyond personal opinions and reach the univeral. The thought rises

above opinion (doxa). But dialogues themselves are just a formal

aspect of dialectics, of which Socrates and Plato is the

inventors.

The first stage of rational knowledge looks as if it were

mathematical, but Plato actually wants to transcend the

mathematical truth. Plato considers the sensible world as one of

appareance in regards of "ideas" themselves, which are objects of

pure thought, intelligible models of all of the things that our

senses do not perceive, but that are much realer and truer than

concrete objects. So he cannot stand the "idea" of bed if it is

not the ideal bed, the real one, that is devised by thought, the

type or paradigm of which wooden beds, iron beds or plain pallets

on the floor are nothing but imitations. In sum, that which Plato

calls "idea" or "essence" (words with similar meanings) is

anything or anybody whenever anything or anybody is imagined in

his mind — Hence, for example, well-known Platonic love; hence our

only possible way of conceiving God, as well.

It is dialectic (concertation) as a well-controlled systematic

itinerary, that from concept to concept and from suggestion to

suggestion makes it possible to reach those ideal "essences" as

well as "good", that is the ultimate goal of rational procedure.

Plato sees "good" as the Divine, which he does not consider as God

the way in which religions think of him, because Plato only counts

the Divine as a principle supreme, superior to life and "essence",

and which is a little more dignified and powerful than them. In

Plato's language "good" is an "idea" which is the cause of all

that is right and "fine"; the "idea" of "good" can be communicated

to anything knowable. The itinerary towards "essences" can only be

understood through the dialectic of "love", notably in "The

Banquet".

What is "love" in Plato's eyes? It is a gap, or a shortage, or

poorness, which shows us how incomplete or hollow we are, it

is a momentum we gather to reach what does not belong in us, a

longing for "beauty" itself. Thanks to "love" we can gain ground

until we get the beauty of the "soul", even though we start from

sensitive bodily beauties, and we incidentally can too get good

social behavior. In the end, a philosopher can reach the ultimate

step and get the very "idea" of the "fine" (or "beautiful") in its

purity and self-sufficiency. It is difficult to say what Plato

means by the "idea" of the "fine" (or "beautiful"). This "idea" is

a unit by itself, it defies corruption, it is distinguished by

absolute purity and transcendency with respect to sensitivity and

other "fatal balderdash". "Beauty" is ultimate disembodiment,

radiance and glory of all that transcends the empirical and the

prectical.

Herein, let us face it, we feel more or less clouded, but aren't

we so whenever we think of Life, or God? We have to

thank Plato for the path, even if is is dark, towards concepts

which had gone barely visible to sinners. The dialectic

of "ideas" dialectic and the theory of "love" lead us to think of

the Platonic idealism (in the strong sense of idealism) as a

doctrine which attributes life per se and independence of mind to

"ideas" or "essences". But we wonder why Plato ventures to make a

theory of "essences".

Maieutics and recollection (or memory) are two main elements which

vindicate the doctrine. Maïeutics is the art of making people's

minds give birth, the art once practiced by Socrates to make his

contact persons discover themselves and become aware of their

inner wealth. This in the "The Menon" is how an ignorant little

slave finds out the right way to make a double square out of

another particular square, because he remembers a calculation

formerly known and practiced. This is the doctrine of recollection

or reminiscence. We deep down hold "ideas" which are just distant

memories. To learn is to recollect the truth once noticed intime

past. The philosophical practice is intended to master and manage

that hidden secret content, which is the fruit of a very distant

contemplation. We call it atavism nowadays.

Plato saws sophists, so-called masters in rhetoric and eloquence,

as liars and dream makers. As a matter of fact, sophists (the

world is still filled with these characters) had eroded the belief

in the absolute, that might have enabled ethics to develop.

Sophists used to say, "Truth is nothing but subjectivity." Their

relativistic doctrine led people to mistakes. Plato's ethics as

truth basics led people to constructive realities, instead. After

the philosopher had gazed at the "ideas", he can go back down into

the "cave" and he now is in a position to develop good ethics and

politics. Through the well-known allegory of the cave Plato

depicts the human condition: Human beings are like prisonniers

chained whith their backs turned on the daylight, who take the

shadows projected onto the wall in front of them for reality. A

prisoner once unchained and led ouside the cave symbolizes the

philosopher that has direct access to "essences". With that in

mind, virtue refers to involvement in "essences" or "ideas" and

real knowledge, a science of good and evil inseparable from

dialectic.

Plato as well as the Hellenic thinking regard virtue and ethics as

elements of knowledge. No one is nasty on purpose. To be brave is

to be aware of whatever is frightening and to face it. To be fair

is to be aware of the harmony of inner force. Real justice has to

represent a just knowledge, therefore. The reasoning part (mind)

in a just "soul" has awareness, is in command, and it overcomes

desire, which is wild and thoughtless (concupiscence) and anger,

which very seldom happens to be the ally of reason. There is no

justice in the city, if the rulers do not change into

philosophers, or if philosophers are not the rulers.

This is the philosophy that has made an impact on the Western

thinking both in analyzing love and desire and in analyzing

speculative plannings. Plato, who died twenty-three centuries ago,

drew paths which have continuously mesmerized civilisation and

culture. He leads us from opinion (lower knowledge, hazy capture

of things that stream out between nothingness and the absolute) to

science (rational knowledge which enables people to come close to

the truth). Our thoughts are still harvesting on the fields that

Socrates and Plato plowed a long time ago.

By saying,"Plato made up philosophy," François Châtelet cannot

stop us from considering Socrates and Plato as partners. Both of

them are not the earliest Greeks who liked common sense better

than myths and the miraculous to understand the world well. There

had been Parmenides, Heraclitus and others, but Socrates and Plato

separates reason from religion, reality from dreaming, so they

represent a fascinating stage on the long way towards metaphysical

honesty, that we Arès Pilgrims are very keen on. Socrates and

Plato make the straightforwardness of the plausible possible, just

as Buddha had made and just as Jesus of Nazareth, Adi Shankara,

Spinoza or The Revelation of Arès fallen down from

Heaven are to make. Nondualism is obvious: Be one within you

(Rev of Arès xxiv/1). We are atoms of unique Life

(24/3-5). Socrates and Plato see plausibility triumphing

and they come close to the notion of Good. But they are

not listened to, because they are not acceptable to religion,

politics, in brief then to all rulers whatever.

Athenian Socrates (469-399) is as rustic as a stonecutter or a

midwife; he does not write anything. Do Plato's dialogues report

on Socrates' thought exactly? Nobody knows, but this is

unimportant. Undoubtedly they compliment each other. As we

most of the time have an erroneous concept of the True,

we need much humbleness to acknowledge our defaults, but both of

them have the humbleness needed really.

The proceedings taken against Socrates by the Athenian Democracy

is the furore that changes Pluto's destiny. As Sorates is

convinced that the soul is part of universal Intelligence,

which is Divine, his incredible serenity in the face of death

shows that he believes in immortality. He drinks the hemlock.

Platon says : "The fairest and wisest of all men has been

murdered!"

The human being locked up in the dark ever since his or her

childhood finds it painful and long to be released. When he or she

is gotten out of the cave — see the parable of the cave in "The

Republic" mentioned above — he or she cannot meet with beauty and

the truth before having been re-educated for a long time. He or

she does not want to return to the cave. He or she might be at

risk there. This is what is penitence that breathes love

into us Arès Pilgrims. Plato writes other fables: Atlantis, and so

on, so that some have considered him as the creator of historical

novels. Actually, Plato uses all the figures that may help

understand whatever reason and language cannot explain.

Freud has his patients speak, in order to help them through a

liberating experience, but it is Plato that introduces the ability

to do so twenty-three centuries earlier, because he is aware that

anybody that speaks and agrees to be objected casts aside the

commonness of feelings, passional dramas, fear od death, the

weight of unbridled traditions and illusory pleasures. François

Chatelet, an expert on Plato, summurizes Plato's forecast by

writing, "There is a possibility, one of pacifying globality, that

skims over all opinions. A universal discourse beyond the control

of oneself revealed by dialectic. Even when men are stupid,

deceitful or untruthful, they keep on liking and willing the truth

clumsily. That willingness to get the truth finds expression in

great demands for non-contradiction. Man worships his own

certainty and consistency. The entry point to set the world in

motion is contradiction."

Some people asked Plato why he wrote overlong passages and

digressions. He repliedt : "Don't be amazed at whatever is

overlong and goes around in circles. One has to circle around

anything great, indeed, because anything great may be subjected to

sliding" (The Republic).

Justice is the ultimate goal, anyway.

Xxxxx xxxx xxx xxx

Signature

Reply :

Xxxx xxx xxx xxx

00xxx00 xxxC2

Xxxx xx xxxx xxx xx x xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxx xx xxx .

Signature.

Reply :

Xxxx xx xxxx xxx xx x xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxx xx xx.